8 Inquiry-based learning activities for the classroom

In this guide

When developing inquiry-based learning activities, it is important to understand what they are and why they are beneficial for students. Inquiry-based learning focuses on problem solving and project based learning.

In contrast to what we would call a “traditional” educational approach, inquiry-based learning does not involve getting the information up front and doing activities based on the teacher given information. Instead, students are given opportunities to explore and to direct their learning. The primary function in inquiry-based learning is students asking and answering questions. Students discover and then ask questions based on their discovery.

The word inquiry implies the use of questioning. Inquiry-based learning, however, is not just the teacher asking questions, but it is about students asking and answering deeper questions about the content.

There are several benefits to using an inquiry-based learning approach in the classroom:

- Inquiry and student led learning increases creativity and curiosity for students. Students learn to think more deeply about a topic.

- Critical thinking skills increase when teachers initiate inquiry-based learning in their classrooms. Students are learning skills that require them to think and question.

- Students experience an increased level of engagement. They are able to direct their own learning and this increases their drive to want to learn. Students are more involved when they are learning content in a way they have chosen.

- Authentic differentiation is possible in a classroom that uses inquiry-based learning activities. Students can work alone or in small groups. A variety of sources can be used by students such as textbooks, computers, other students, books, magazines, etc. Students are often able to determine how they want to present their learning which is a way of offering choice.

In a previous blog, I wrote about differentiation and adaptive teaching. Inquiry-based learning activities are useful in either approach. Both require that a teacher address student needs through formative assessment. Inquiry-based strategies are a great way to identify student needs and adjust instruction or activities according to those needs.

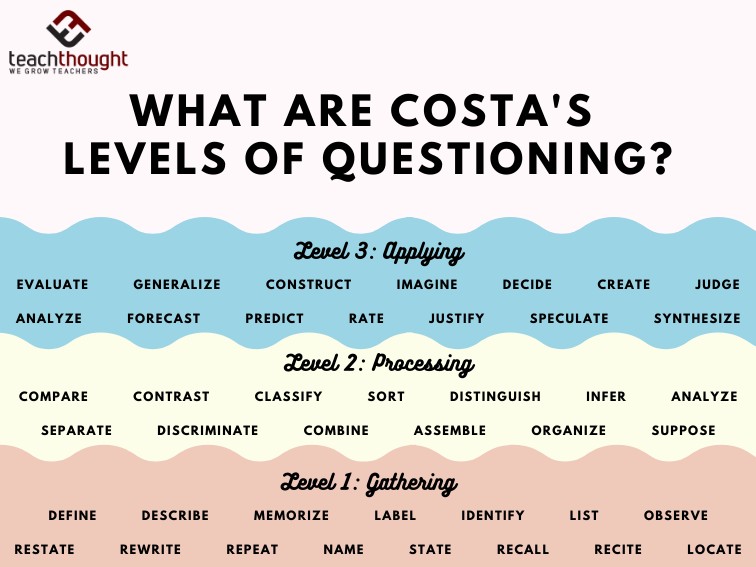

When developing activities for inquiry-based learning, something to consider is levels of questioning and thinking. Inquiry is about questioning, but there are different levels of questions that can be asked.

Last school year, I taught a class called AVID. AVID stands for Advancement Via Individual Determination and it is a college preparation course that teaches students organizational, inquiry, and behavioral skills.

AVID uses Costa’s Levels of Thinking to push students and teachers to create deeper questions and to think critically.

There are three levels to Costa’s:

- Level 1 is gathering information. This is information that is on the page and readily available. Level 1 information does not require critical thinking.

- Level 2 is processing information. This information requires the reader to read between the lines and make inferences.

- Level 3 is applying information. The reader must take information and apply it to a new situation or make generalizations about the information presented.

In AVID, we used Costa’s to increase rigor and to teach students how to think at a deeper level. Students are taught Costa’s and how to develop questions for use in classroom discussions and in their own inquiry-based activities.

Another leveling system that is often used is Bloom’s Taxonomy. Below is an example of verbs derived from the different levels of Bloom’s. These increase in rigor as you move through the levels.

Regardless of which system is used, it is important for students to develop questioning skills.

Not only should teachers use various levels of questioning, but students should also learn how to develop higher order thinking questions. Teaching students to recognize deeper questions, how to address them, and how to develop their own questions is vital to producing critical thinkers.

This article includes eight examples of inquiry-based learning activities. I have attempted to include activities that can work with any age group. Ways that the activity can be modified for student needs has also been included where necessary.

1) Experiments

One very common example of an inquiry-based learning activity is an experiment. Allowing students to conduct an experiment – including developing and testing a hypothesis is an excellent way to include inquiry-based learning in your classroom.

Here are some examples of experiments (that aren’t science).

History

- Students can choose a historical event and form a “hypothesis” for what would happen if that historical event had unfolded in a different way. For example – What would have happened if Thomas Jefferson did not write the Declaration of Independence? How would the world look different if the colonies had lost the American Revolution?

- Using historical references, documents, and their own creativity students can create a product to present the results of their “experiment”.

- The teacher can also present a historical event and allow students to develop their own questions to research.

This ClickView series follows students as they conduct a historical inquiry. The videos give a good overview of what historical inquiry can look like in the classroom.

Math

- Students can be presented a problem based on the content being learned or based on questions they or other students have.

- The student investigation would not only include how to solve the problem, but if there are multiple ways to solve the problem, real life implications for the problem, and how this problem could be changed to vary the answer or outcome.

ELA

- In a reading or ELA classroom, students can “investigate” how changing a character’s traits impacts a story. They can rewrite the story’s ending or a scene from the text with the changes. Their “research” will share evidence of how changing the character can change the text’s meaning or implications.

Conducting experiments can be modified for any group of students, regardless of age or abilities.

2) Classroom dialogue

Conducting a classroom dialogue is another way to incorporate inquiry-based learning. Many times these are referred to as classroom debates, however, there are distinct differences between a debate and a dialogue.

Debate vs. dialogue

- A dialogue is collaborative – the purpose is to deepen understanding, not win an argument.

- A debate focuses on evidence and proving how one side is right, but a dialogue seeks to find solutions to problems.

- A dialogue is open ended, but a debate comes to a distinct conclusion.

- In a dialogue, students are learning and deepening their understanding of subject matter. In a debate, students learn how to prove a point, but may only deepen their understanding of one side.

Both dialogues and debates serve their purposes in the classroom, but dialogue is more conducive to an inquiry-based approach.

A classroom dialogue requires both the students and the teacher to prepare for the discussion. The students must spend time learning about the subject and creating questions to drive the dialogue. Using concept maps can help students to connect their knowledge and help students develop questions.

The teacher must also prepare for the classroom dialogue. The teacher does not necessarily facilitate the discussion or provide all of the questions, but can help to move the dialogue forward.

The teacher should:

- Plan significant questions to provide meaning and direction

- Draw as many students as possible into the discussion

- Allow at least thirty seconds for students to respond

- Follow up on students’ responses

- Periodically summarize in writing key points that have been discussed

The teacher’s job is to help focus the discussion and to help students learn how to have constructive conversations.

A suggestion I would give with an activity like classroom dialogues is to try it more than once. Often the first time trying an activity with students, especially one that requires active participation and critical thinking, it can be messy. Reflecting on the activity and making adjustments where needed can make the second attempt more successful.

3) My favorite mistake

This activity is one that a fellow teacher relayed to me. He uses this activity in his classroom as a warm up during the week. He calls it “My Favorite Mistake”. It is a math activity, but could be changed for any content area.

- At the beginning of the week, students anonymously answer a teacher given problem on an index card.

- The teacher collects the index cards and looks through them to identify mistakes.

- Each day, the teacher chooses a card or group of cards that has a mistake or concern the teacher wants to address.

- The teacher displays the problem on the board and announces that this card contains “my favorite mistake”.

- Students analyze the card or group of cards to find the mistake.

- The class then discusses what correction needs to be made and what information can be used to avoid the mistake in the future.

This activity serves multiple purposes.

- The teacher can use the index cards as a form of formative assessment to guide future instruction.

- Students are required to think critically and identify patterns within problems.

- Through this type of activity students learn that “failure is an important part of the problem-solving process” (Australian Government Department of Education).

This activity can be modified for any subject matter by replacing the math problem with an appropriate task or problem. For example, in an ELA course, students could write a sentence using a specific grammar rule or figurative language.

4) Objects and artifacts

In a typical classroom, teachers may bring in objects or artifacts that are relevant to the lesson being taught. For example, years ago I taught middle school US History. When we learned about the Boston Massacre, I would bring pictures to show students.

When learning about the Boston Massacre and the American Revolution in general, we learned about propaganda and its purposes. This picture is often shown as an example of how the American colonies fueled mistrust, fear, and anger for the British Redcoats.

I would use pictures like this and have students create questions that they have after viewing these pictures. These questions would be used to spark classroom discussions. After these discussions, students would investigate further and create written responses to their questions.

Another way to use artifacts is to present them to students with no or limited context. Students then create questions and draw their own conclusions about the purposes of and relationships between the items presented.

5) Jigsaw learning

Jigsaw activities allow students to become experts on a topic and then teach that topic to others.

In a jigsaw activity, student groups are given a text to read. This text is broken up into smaller chunks. Groups are assigned a section to read and become an “expert” on. As they are reading their section, students take notes, discuss important points, and develop questions they have regarding the text.

After becoming experts, each section shares what they have learned with the other groups. The sharing portion of the activity can be done in different ways depending on your classroom and time restraints.

- Each group shares with the entire class. They create a poster with information from their text section and share. The class takes notes and records important information from each group.

- One member from each group rotates between the groups and becomes an expert on each section. They return to their home group and share important information with their group.

- If students have created posters or other visuals regarding their section, students can do a gallery walk to learn about the other sections.

Once students have learned about each section, they make connections between the sections to understand the text as a whole.

6) Question development

Developing students’ ability to think deeper and ask critical questions is a valuable skill. This activity uses Costa’s Levels of Thinking to teach students how to develop questions at various levels.

This activity requires that students develop deeper questioning skills. Inquiry-based learning is not just about students answering questions, but also about increasing their ability to ask questions.

In my own classroom, we used Costa’s Levels of Thinking, however, Bloom’s can also be used. The ultimate goal is to teach students to think deeper, regardless of what list of words are used.

I have done this activity with both students and with fellow teachers during professional development.

Students will develop questions using the assigned level from Costa’s or Bloom’s:

- Divide students into partners/groups.

- Each group will determine a recorder for the group. This person’s job is to write down all of the questions the group creates.

- The teacher gives the students an object or subject to consider.

- The first time you do this activity, it helps to choose a subject that is easier for students to address such as crayons or subtraction. Then, move to a more specific subject that is appropriate to your lesson such as personification or subtracting decimals.

- The teacher also gives the students a level at which to create questions. Using either Costa’s or Bloom’s Taxonomy assign a level for questioning.

- On a piece of paper, students develop as many statements or questions about the subject at the appropriate level. Students can use the verbs from the level to create their questions. Ideally, students would have access to a visual of Costa’s or Bloom’s such as the ones given above.

An example:

- The subject is crayons.

- The level is 3 (Costa’s).

Potential statements or questions developed from the example:

- Compare the red crayon and the blue crayon.

- If you were to classify the crayons in a box, what would your categories be?

- Explain why crayons are useful in the classroom.

Remember, that students are not necessarily answering their own questions, but they are learning about ways to develop questions and observations at a higher level.

Once students understand how to do this activity with something easier like crayons, the teacher can give harder subjects such as polynomials, the food chain, or metaphors.

7) Concept maps

Concept maps help students to connect their learning to information they already know and helps them to develop questions for further research. Students can use their concept maps to develop questions they still have about materials, to study, and to connect what they have learned to future materials.

When students develop concept maps, they must “visualize their prior knowledge” and this helps them to recognize what they have learned and what they still need to learn.

When teaching concept mapping to students, it is important to model how to create a concept map. Creating a concept map as a whole class can help students learn this skill within a supportive context. Many students may need scaffolding support before they are able to create in depth concept maps.

Students need to learn the concepts behind reading a chart or diagram before successfully creating their own. It can take time for students to learn what a concept map is, but with repeated exposure and scaffolded examples, they can learn to create them on their own.

It is also important to remember that students should make their concept maps in a way that is beneficial to them. Their concept map may not look like the teachers, or their maps may begin to evolve as they attain more knowledge and skills.

Concept maps can look different for various classroom purposes and grade levels as well. They can be individual or group activities.

The Learning Center at the University of North Carolina Chapel Hill has several examples of concept maps that can be modified for different student needs.

One idea that I came across for group created concept maps was for each person to use a different color on the concept map. This allows the group members and the teacher to observe each student’s thinking and their contributions.

8) Inquiry through construction

This activity is a great way to introduce inquiry-based learning in a non-threatening and inclusive way. Any student at any grade level can participate and learn from this activity.

Provide students with various materials for building a marble run. Materials can include empty toilet paper and paper towel rolls, wooden craft sticks, cardboard boxes/pieces of various sizes, tape, glue, and scissors.

Students are then given time to build a functioning marble run. They can test different lengths and widths of materials.

This activity encourages students to think critically, be creative, and to learn from mistakes. When students have completed the activity they can reflect on what worked, what didn’t, and how they can apply these skills to other situations. They can even conduct research on ways to create a better marble run.

A variation of this activity, that I have done in my classroom, is creating marshmallow towers. I did this activity with middle school students and they not only learned problem solving, but they also worked on team building skills.

- Place students in small groups of 3-5 students.

- Give students a paper plate, 150 toothpicks, and a baggie of 100 marshmallows.

- Set a timer for 5 minutes.

- Students work together to build the tallest tower.

- At the end of the time, give students 3 minutes to discuss how to improve their tower.

- Set a timer for 5 more minutes.

- Students spend this time improving their tower to try to build the tallest tower.

These hands-on activities are a fun way to incorporate inquiry in a way that students can analyze their work, improve their skills, and learn from their mistakes.

Inquiry-based learning is a way to increase students’ critical thinking skills. Students need to learn to think deeper, learn from their mistakes, and communicate about their learning. The above activities provide a few ways for this learning to occur in your classroom and will hopefully inspire more inquiry-based learning in the future.

Sources

- Academically and Intellectually Gifted Handbook for Teachers. Costa’s and Bloom’s Taxonomy. Available at https://macsaigteacher.weebly.com/costa-and-blooms.html (Accessed June 30, 2024).

- Australian Government Department of Education (2023). Inquiry-based learning. Available at https://www.education.gov.au/australian-curriculum/national-stem-education-resources-toolkit/i-want-know-about-stem-education/what-works-best-when-teaching-stem/inquiry-based-learning. (Accessed June 30, 2024).

- AVID (2024). Costa’s Levels of Thinking. Available at https://avidopenaccess.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/Costas-Levels-of-Inquiry.pdf (Accessed June 30, 2024).

- Grand Canyon University (2023). 6 Benefits of Inquiry-Based Learning in the Classroom. Available at https://www.gcu.edu/blog/teaching-school-administration/6-benefits-inquiry-based-learning-classroom (Accessed June 29, 2024).

- Norfolk State University (2023). How Inquiry Based Learning Can Work in a Math Classroom. Available at https://online.nsu.edu/degrees/education/masters-urban/mathematics/inquiry-based-learning-math-classroom/ (Accessed June 30, 2024).

- Rice University, Office of Undergraduate Research and Inquiry. Pedagogy of Inquiry. Available at https://ouri.rice.edu/faculty-resources/pedagogy-inquiry (Accessed 29 July 2024).

- The Learning Center, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill (2024). Concept Maps. Available at https://learningcenter.unc.edu/tips-and-tools/using-concept-maps/ (Accessed June 29, 2024).

- University of Connecticut Center for Excellence in Teaching and Learning. Socratic Questions. Available at https://cetl.uconn.edu/resources/teaching-your-course/leading-effective-discussions/socratic-questions/ (Accessed June 30, 2024).

- Zwaal, W. , & Otting, H. (2012). The Impact of Concept Mapping on the Process of Problem-based Learning. Interdisciplinary Journal of Problem-Based Learning, 6(1).Available at: https://doi.org/10.7771/1541-5015.1314

Mattie Farrer

briefcase iconAVID Site Coordinator / Content Curator

Mattie Farrer has been an educator in various grade levels and capacities during her career. She has a passion for supporting English learners and their language development. She also loves helping teachers reach all students.

Other posts

Want more content like this?

Subscribe for blog updates, monthly video releases, trending topics, and exclusive content delivered straight to your inbox.